Chris Carmen / October 2, 2025

The state, along with California and New York, has seen an exodus. But it’s not all to Texas and it’s not all about taxes, writes Justin Fox of Bloomberg Opinion.

JUSTIN FOX

Bloomberg Opinion

New York, California and Illinois have been hemorrhaging residents. Almost 3.2 million more people left those states for elsewhere in the U.S. than arrived from other states, from 2010 through 2019, according to population estimates released last week by the Census Bureau.

Nine other states saw net out-migration of more than 100,000 people over that period, but none really came close to the big three.

Thanks to 2 million more births than deaths and 1 million newcomers from other countries, California’s population still grew by about 2 million over this period, a gain that trailed only those of Texas and Florida. New York’s population grew but only slightly, while Illinois lost an estimated 159,751 people between 2010 and 2019.

Yes, these are all big states, but New York and Illinois ranked second and third in net domestic migration as percentage of 2010 population, behind only Alaska (California ranked 13th).

Where are all these people going?

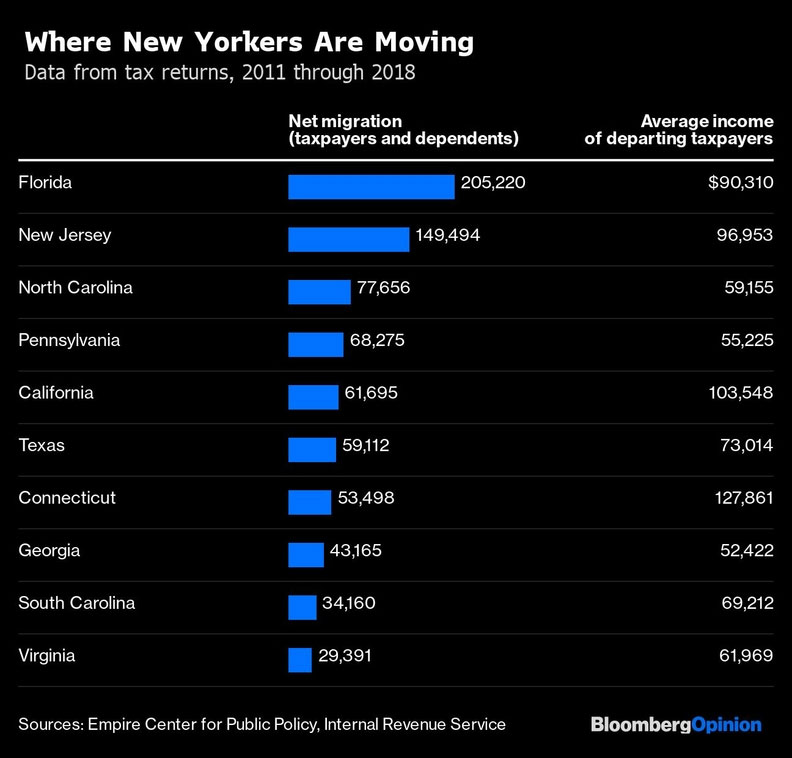

The Empire Center for Public Policy, a conservative Albany think tank, put together some estimates for New York based on data that the Internal Revenue Service gleans from tax returns. (The Census Bureau also releases data on state-to-state migration flows, but those are based on surveys with sometimes-large margins of error, so the IRS numbers are more reliable if less complete.)

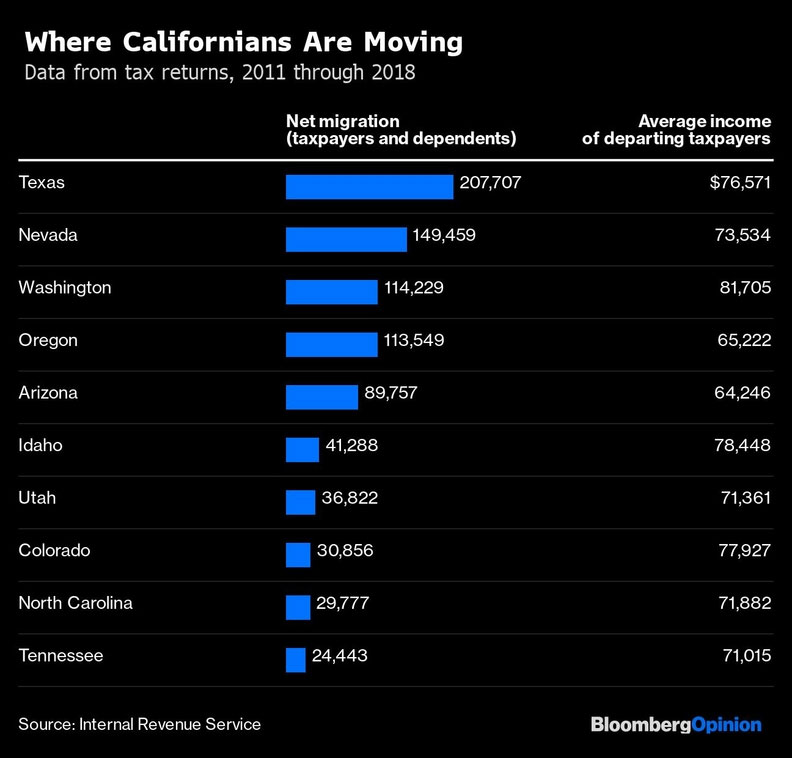

This inspired me to do the same for California and Illinois. Here are the Empire Center’s numbers for New York:

The adjusted gross income of New York taxpayers who didn’t migrate averaged $88,940 from 2012 through 2018. Those who left for Florida, New Jersey, California and Connecticut made more money than that; those who moved to other states in the top 10 less, in some cases much less.

By far the most affluent group of migrants from New York was the 1,309 taxpayers who moved to Wyoming, who had an average income of $179,014.

The adjusted gross income of California taxpayers who didn’t migrate averaged $84,641, and migrants to all of the top-10 states made less than that.

Also notable in California’s case is that it experienced net inflows from about half the states, including New York and Illinois. It’s losing residents in huge numbers to nearby states, but still attracting people from the Northeast and Midwest.

Finally, here’s where Illinoisans have been going.

The adjusted gross income of Illinois taxpayers who didn’t migrate averaged $78,959. Illinois has been losing high-income residents (a lot of them retirees, one imagines) to Florida, middle-income residents to the South and West, and those with lower incomes to neighboring https://viasilden.com states. Also, the top two destinations for Illinois migrants are the top two for the nation as a whole, with Florida first, Texas second.

Domestic migration statistics are frequently cited as evidence of the failures of blue-state governance, in particular the higher taxes imposed by states that are losing lots of residents. There’s something to that—income-tax-free Florida sure is attracting a lot of affluent people from Illinois and New York, and a recent study of high-income California taxpayers concluded that a 2012 income tax increase there did in fact drive some away. But California, Illinois and New York have all experienced bigger per capita personal income gains than the nation as a whole since the beginning of 2010, and all saw taxpayers with incomes below $50,000 overrepresented among the leavers from 2011 through 2018. These departures may indicate failures of governance as well, but it’s a different set of governance failures, presumably related more to housing costs, commutes and job opportunities than taxes per se.

There also isn’t much evidence in the IRS data—yet—of an exodus of high-income taxpayers hit by the state-and-local-tax-deduction limits imposed by the 2017 tax bill. That is, the number of taxpayers with adjusted gross incomes of $200,000 or more leaving for other states actually fell in high-tax California, Connecticut, Illinois, New Jersey and New York from 2017 to 2018, the year the cap went into effect. Those who ended up with higher tax bills due to the change generally didn’t find out exactly how much higher until 2019, though, so it may just be too early to tell.

One last thing I checked was which counties in New York have been sending the most migrants to other states. My fellow Bloomberg Opinion columnist Conor Sen argued this week that in congressional-redistricting terms the most important population shifts of recent years have been from rural areas to large metropolitan areas, not from state to state. Indeed, thanks to babies and immigrants, New York City and most of its suburbs have gained population over the past decade as the rest of the state has shrunk. That may be changing, though, as the city in particular has been seeing accelerating migration to other states. Of those who left New York state from 2011 to 2012, 49.1% were from the city. From 2017 to 2018, 68.4% were. A lot of those people are just moving to New Jersey. But it’s not a great sign.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

« Previous Next »